Selle Valley Reverie: A Childhood Steeped in Tradition

By Meyla Bianco Johnston

I was fortunate to grow up in the Selle Valley from the fourth grade on, attending Northside Elementary School just about a mile from my family’s home as a girl. I graduated from Sandpoint High School and later, the University of Idaho.

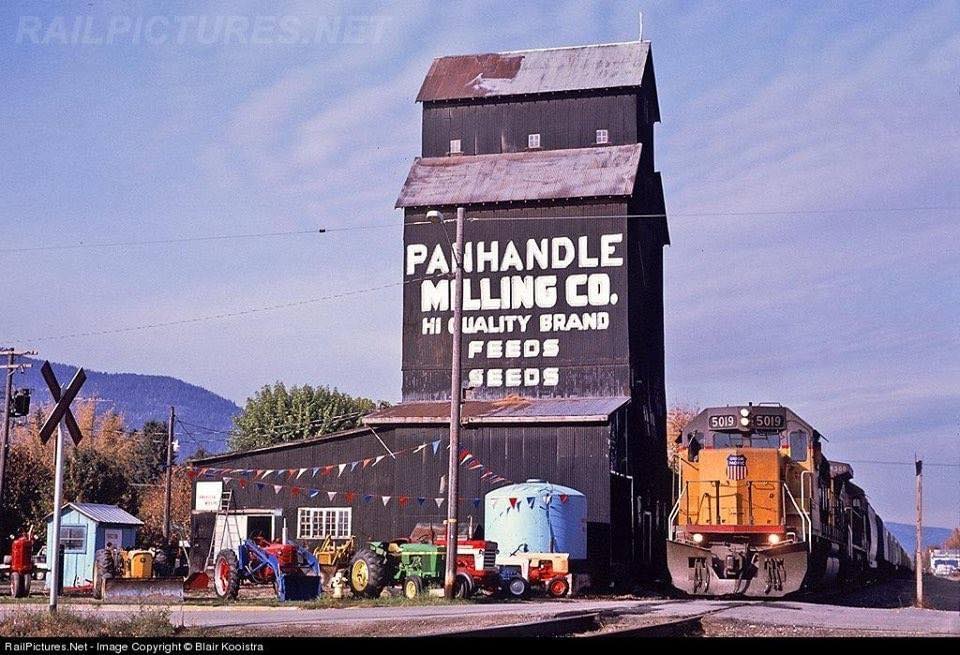

When I was a kid, Colburn Culver Road was called Farm to Market Road — the farmers took their goods that way toward Sandpoint to sell. The rural, agricultural valley was full of people who raised their own food and got involved in the Selle and Oden granges and churches, schools and Sandpoint athletic teams. We had a party line and had to wait our turn to make calls. Our TV got two channels.

My family understood early that community matters if you wanted to make it in North Idaho. We had planned and saved for years to come here and arrived in 1979. We needed to rely on each other to get things done and to make it though winter. In 1980, the economy was tough. Families had to be frugal and smart.

I learned so much from our across-the-street neighbors Alvin and Vivian Jacobson and their extended family, Elmer and Ina Jacobson— things that made me who I am today.

I would guess that there are not many Americans lucky enough to hear the history that I routinely did as a Northside kid. Stories of when Alvin cleared the land of cedar stumps with his team of draft horses and dynamite, how the Native Americans gathered by Lake Pend Oreille in summer and when Colburn Culver Road was what Vivian called a “dirt trail.”

Photo courtesy United States Library of Congress

I was told Alvin bought his land on Colburn Culver when he was 16, a full section for just $1.25 an acre. We helped hay that land in summer in long sleeves and blazing heat, putting each bale on the finicky elevator up, up, up to the top of the tall barn with the hawk’s beak. Mid-day, we got to eat “dinner” at Vivian’s fully-laden table, getting introduced to an incredible strawberry-rhubarb dessert in shallow Melamine dishes that lives on in family lore.

We watched Alvin clean huckleberries with his homemade contraption that also sized them, knowing he might have picked the berries with bears sharing in the summer feast just feet away.

I was fascinated by the chute to the Jacobson’s basement where he dropped the split firewood for the furnace. The dark corners down there were full of abandoned, old-timey stuff and it smelled like the past.

Upstairs, I admired Vivian’s African violets in margarine tubs on each windowsill and watched them sparkle in the winter sunlight. Vivian made sure we had Black Eyed Susans from her patch (they’re still going strong at our place) and invited my sister and I to get in on craft days with the older farmer’s wives to make yarn pom-pom kitties in little baskets — we were thrilled!

When Alvin kept trying for litters of all-white barn cats, my sister and I benefitted by adopting the little, wild almost-white kitties — with disqualifying grey spots. You had to handle them with fireplace gauntlets, but still, we loved them!

The Jacobsons generously helped us with countless projects at our house — with little ceremony or fuss. They worked so hard to create a living for their family, consistently making something out of nothing until they had enough.

We could depend on their solid advice, generously given. Helping each other was the code and way of life.

Later, when I was about nineteen, it was time to chop wood at our house and our family was hard at work. Alvin materialized, as he often did, steadily working with little comment. It was hot and we were all working up a sweat, hustling because we wanted to get it done. After some time, my Dad asked Alvin if he wanted a drink of water. Alvin wryly commented, “I ain’t dry yet.” After a good laugh at the tenacity of the old man working circles around us, the rest of us drank deeply. I believe Alvin must have been in his eighties at the time.

I could tell you a dozen funny stories about the Jacobsons, their plainspoken practicality, their grit, and most of all, their generous humanity.

The Jacobsons were just one family part of a larger network of other families from the Selle Valley of my youth. Each one has a valuable history and each navigated challenging circumstances within a community that had their back. I feel so grateful that I had the chance to learn from them by being immersed in such a powerful model.

As I drive down Colburn Culver Road, the stories flood my senses, even today.

There is the shack Alvin’s parents built to live through the first winter, which the current resident uses as a garden shed. Do they know its past? There is where the corn was always knee high by the Fourth of July (while ours was knee high to a grasshopper).

There is where my schoolmate Doug Kennedy lived with the curly forelock, just like the Hereford steer his parents raised.

That land is where Jackie served us tiny little loaves of delicious zucchini bread while I read the I Shalt Not Race the Train prayer on the wall, over and over again. There is the Pack River Cemetery where George, the resident dowser, chicken and well casing man enjoys his well-earned eternal rest with many of the other old timers I knew as a girl.

There is the riverbank where we painted ourselves with clay then stayed motionless until it was time to crack it off in a wild fit of dancing. There is where the ring of cedars once stood, where we found the dead porcupine and picked quills from my friends’ dogs’ noses. There is my best friend Candy’s enormous barn, where in summer we lay in the fields, braid tips brushing the earth, quietly watching the deer come into the fields at dusk to browse.

There are the shiny-beautiful coal-black Percherons, grazing with gentle eyes and square hooves, giving us a new Roman-nosed baby with fuzzy mane and puff tail each year. Each October, we watched them at the International Draft Horse Show where I learned the words to O Canada.

With a nip in the air as delicious as the hot cocoa we sipped by the fence, we were thrilled by the thunder they made as they passed by, necks arched, accompanied by jaunty organ music courtesy of the little old lady in the booth.

I can still feel the excitement and stiffness of the brand new jeans I wore to the Bonner County Fair along with tightly braided hair that pulled my eyes back just a little bit.

These memories crystallize the beauty, love and reality of my childhood in the Selle Valley in my mind forever.

These days, my husband and I are fortunate to own properties and businesses in Bonner County and to work and to live in the incredible Selle Valley. We follow the unwritten rural rules which most often just means minding our own business, being polite and waving when you’re driving down a gravel road. We ask that our neighbors respect our privacy and we do the same for them. We pay attention to fences and always, if in doubt, ask permission first. That’s what you learn growing up in the Selle Valley.

Bonner County Idaho’s Selle Valley is one of the most unique and beautiful places on earth.

The famous photographer Dorothea Lange, traveling during the Depression in the 1930s to document American life for the Civilian Conservation Corps, thought Bonner County was outstanding enough to capture on film — look for her 1930s image of rural mailboxes against a stormy sky for an enduring snapshot of what the Selle Valley means. It shows hand-lettered arrows that point toward Grouse Creek, Lightning Creek, what was then called the Pack River School, Gold Creek, Oden and Kootenai.

Photo courtesy United States Library of Congress

Where do the signposts lead us today? My sincere hope is that we choose the road that leads away from dense development, away from maximum profit and toward family togetherness, raising animals and eating from the garden. If kids can grow up respecting outside spaces, wildlife and each other, we can hold on to the best parts of rural America. They can be productive citizens who know how to make and fix things, how to care for animals and also how to show compassion to a neighbor in need.

I want to live in a Selle Valley where the people really understand the history of the area and treat each other with respect, even if their opinions differ. My sincere hope is that neighbors, friends and citizens of Bonner County don’t forget the good and hardworking people who came before us and paved the way for our ease.

I hope we as a community consider our future growth carefully and decide how we want Sandpoint’s rural areas to look and feel in the future. Preserving a valuable heritage like this will take work, guts and even compromise.

I guess the simplest test of whether we’re thinking right is to consider what the old timers would think of what we are doing, how we are treating the land and the wildlife . . . and make our plans accordingly.